That such a cache of mundane and some might say, pedestrian letters should survive so many years continues to amaze and delight me. The earliest ones date from the 1830s and were exchanged between members of the George family, Ann's mother Jane's side of the family.

James George, Ann’s grandfather, originally came from

Horningsham, a small village four miles from Warminster in Wiltshire. He was employed for sixty years as a land

agent for the wealthy Talbot family, responsible for collecting

rents from the tenants of the extensive Penrice estate.

The George family lived at Nicholaston Hall in a village of

the same name overlooking Oxwich Bay.

The family must have been on the move at the time of Jane’s birth as she

was baptised on May 13, 1802 at Dailly in Ayrshire. The other six children were all baptised at

St. Andrew’s Church, Penrice – Thomas in 1788; Hannah 1790; John 1791; Harriet

1795; James 1797; Mary 1793 and Robert in 1799.

Harriet George married Samuel Gibbs, a seaman from Porteynon, at St Nicholas Church, Nicholaston on January 30, 1816. The couple set up home in the village of Porteynon where their nine children were baptised at the parish church of St. Cattwg.

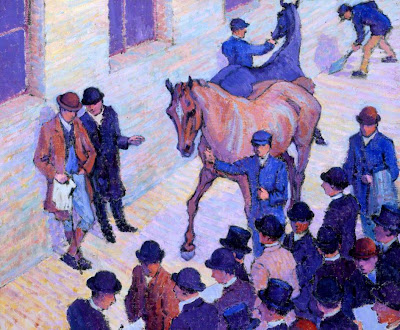

Perhaps this inclination to preserve family letters and ephemera was a George characteristic. Harriet kept a series of little notebooks in which she recorded family events. In 1854 there is a reference to her sister Jane. Bevan. She notes that the family at Oxwich Castle "are quite well and they have had an abundant harvest. It has been a fine time on the farm, the live and dead stock fetching such high prices owing to the Russian War, which is not likely to terminate soon." She also kept a batch of letters received from her scattered family over the years, which she read on her regular walks along the cliffs.

One of Harriet's sons, George, was appointed Lloyd's Agent in Gower in 1864 and in one of her several notebooks Harriet records some of the shipwrecks George attends.

February 10, 1864.

A brigatin got ashore out by Skysie and became a total wreck, she belonged to Port Talbot, came from Plymouth with limestone ballast, her name "The Perie," 200 tons, all saved their lives, 5 of the crew lodged a J. bevan and boarded till Friday the following, the 12th. The Captain lodged at our house until the Wednesday and he left. We charged him nothing for his board. He was a quiet, inoffensive man, not married, a Capt. Gidies. Their board at "The Ship" came to £1.0.0.

September, 19, 1864.

A large brig, name "Industry," came out from LLanelly with coals and sprung a leak. They run her in on the sand at Nackershole, and there she is and will not likely to be got off, they were bound to Malta.

September 20, 1864.

The cargo is insured in Loyd's and George Gibbs being the agent, he had to discharge it and save all he can and sell it.

February 6, 1867.

The French lugger came ashore on Brufton sand called the "Fortuna," laden with cotton and a few barrels of sugar.

March 10, 1867

Sunday night, at 1 o'clock a large brig, 300 tons, stuck on

Porteynon point and became a total wreck, in ballast, bound to Cardiff for Coal

from Whitstable, name Amininoe. There was at this time a fall of snow and East

wind, and the Captain and crew, 7 men, had to stay in the place until 14th,

when they all went in Grove's bus, and G. Gibbs with them being Loyd's agent.

January 23, 1868.

At 2 o'clock in the morning, George Gibbs was sent for to

Rosilly, a vessel ashore and all perished. It was an awful gale, and sea

running mountains. There was a heart-rending scene to look at, 11 vessels all

to pieces, having come out of Lanelly in the evening and the wind died away,

the sea mad and they all got ashore on Rosilly sand and Llangenny, Brufton and

the banks. The shore was all strewed with the wrecks, 15 tun vessells came

out and 11 can be seen the remains; the others are supposed to be gone

and the crews of them as they left the vessels and some of them got to the

hulk. How many poor fellows is gone, the account is not known. This is the most

distressing wreck that was ever heard of on this coast."

Harriet's story is told in an article written by Michael

Gibbs entitled "Dear Stay At Home," published in the Gower Journal

Vol 34 in 1983. He concludes:

"Harriet survived her husband by more than eleven years. She died on the 13th November, 1881. When the time came to sort out her personal effects, her daughter Lizzie carefully packed together the letters and the little notebooks which Harriet had kept, and preserved them. If she had consigned them to the fire, as many people would have done, none of this could have been written."

When Dr Mary Bevan died in 2004 in Mildura, Western Australia this bundle of Bevan family letters could also so easily have ended up on a fire with a whole family history lost.

You might also like to read

Frank decides on being a draper - or not